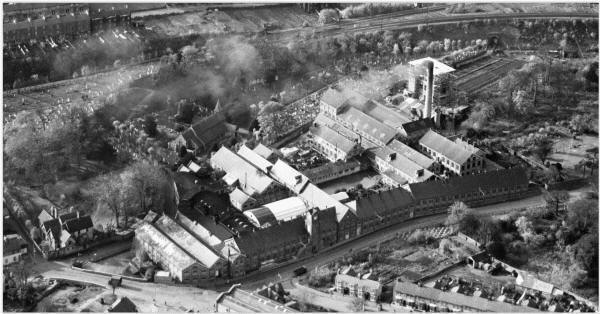

Buckland Paper Mill

Photo 1947

There have been two paper mills at Buckland, Buckland Paper Mill and Lower Buckland Mill which was situated at the rear of Mannerings Flour Mill. Early records referring to papermaking in Buckland do not differentiate between the two mills and thus it has been necessary to ascertain the date when at least one of them was established in order to determine to which mill these early records apply. CP Davies found that Lower Buckland Mill belonged to " Henry Pain of Buckland, miller " in 1747 he having married the previous owners widow, and that it remained in the possession of the family for some fifty years. Davies also states that it was Henry Pain who commenced making paper here and that a deed of August 1775 peaks of "the mill house stables water mill and paper mill (the latter lately erected) ". On this evidence it is accepted that historical records relating to papermaking prior to the 1770s refer to Buckland Paper Mill.

The first reference to a Buckland Mill is to be found in an old Dover Charter, No. 72, dated 1451, which deals with the "release" of land named the " Mill Land lying in Buckland to Sir (Rev) Thomas Moys, Master of the House of God, Dover ". This was probably a corn mill and may have some connection with the development of the paper mill in later years.

CP Davies first mentions Buckland Mill when he states "From the accounts of Prior Lenham (1530-1) it appears that a mill at Buckland was let for ten shillings a year ", and later, in the last quarter of the sixteenth century, an undated "....note of the farm rents belonging to the Priory-lease of Dover " has " Buckland Mill, now Persey, leased to John Parker and payeth yearly li.x. " The first mention of papermaking in the parish of Buckland comes in 1638 when " Thomas Chapman, a papermaker of Buckland, was married ".

In 1705 another papermaker, John King of Buckland, was married. In 1746 the Folkestone Overseers of the Poor apprenticed a boy named Isaac Crump to Thomas and Ingram Horn. There is no mention of the trade to which this boy was apprenticed but it may be assumed to have been that of papermaking. In the same year, 1746, Thomas Horn, the elder, millwright, was lessee of both Buckland and Charlton mills and in his will of that date, (proved in 1750), thus disposes of them:

" Also I give and bequeath unto my two Sons Thomas and Ingram equally to be divided between them all those my two mills called Buckland and Charlton Mills (Holden by lease from His Grace the Archbishop of Canterbury for a certain of years) ".

The date of the death of Thomas Horn the elder, is not known but it can be assumed that his two sons were taking over the business when Isaac Crump was indentured. The relationship between the two sons (Thomas and Ingram) in reference to the operation of the business bequeathed to them by their father, is not known, but later records indicate that it was close, with Ingram devoting himself to the papermaking side for in 1770 he is recorded as being the occupier of Buckland Mill, although his name appears in the deeds of the Town (corn) Mill in 1767.

In 1770 an artist, (T. Forest) painted a watercolour of " Buckland Paper Mill from the Churchyard", the original of which is in the possession of the Hobday family. The painting depicts a two story house with three dormer windows on the first floor and several annexes built onto the main building on the ground floor. It shows the shaft of a water wheel entering the building at one end. It would appear to indicate that paper- making as practiced by the Horn family in the 18th century was that of a cottage industry.

It is known that Thomas Horn died between 1745 and 1750 at which time he operated Buckland Paper Mill and Charlton Corn Mill and it would appear reasonable to assume that he may have been in business in the area for some years to have established two businesses. Thomas (the elder) was a millwright which suggests that he was primarily a papermaker and he may have extended his activities to corn milling to provide an occupation for one of his two sons, apparently Thomas (2). The name ‘Thomas’ occurs in the records of Buckland through to 1823 when Thomas Horn built Buckland House. There is no record of either Thomas (2) or Ingram Horn having married unless it is in the Church Register but it is considered that one of them did marry and had a son, who in turn was named Thomas and it was he who built Buckland House on his retirement from business in the early part of the 19th century.

In 1784 Thomas Horn made an application for the Freedom of Dover, describing himself as a miller, between the years 1791 and 1803 Thomas advertised several times for millers. This was probably Thomas (3). Ingram Horn however had an interest in milling for he appears to have bought the Town Mill in 1767 being described in the deeds of the property as " millwright, one of the sons of Thomas Horn of Dover millwright deceased ". This corn mill passed to Thomas Horn (3—?) about 1800 who rebuilt it and in the following year advertised for " two journeymen millers; one a stone-dresser and the other a flour dresser ". This Thomas Horn was surely Thomas (5) for both Thomas and Ingram, sons of the oldest known Thomas must have been elderly, and indeed Thomas (2) may well have been dead, in 1800 over fifty years after the death of their father. The Town Mill was situated near Dover Harbour " where boys and vessels are constantly employed to and from London and coastwise, afford an opportunity of carrying on the trade upon a most extensive scale ". The mill was sold in 1804, the advertisement for the sale saying that Thomas Horn was " retiring from the milling and corn trades ".

In 1805 Thomas Horn built an oil mill at Charlton presumably on the site of the corn mill bequeathed to the brothers by their father. Although there is no record of the death of Thomas Horn (2) it is considered that the Thomas referred to above was of the third generation although it is known that Ingram was alive at the time.

In 1799 the Horns bought Buckland Mill and Charlton Mill from the Archbishop of Canterbury for £822. 10s having previously leased them on a beneficial lease of £5. 10s. It would appear that the properties had been divided between Ingram and Thomas (2) for a conveyance of the Buckland property many years later refer to Ingram as the occupier thus, formerly in the occupation of Ingram Horn afterwards Thomas Horn afterwards of the said Charles Ashdown and later in the document, hitherto enjoyed by the said Ingram Horn, Thomas Horn, Ann Born (probably widow of Thomas (3), ‘William Hussey fleet, Thomas Horn fleet. It may be assumed that Thomas (3) inherited the mill from Ingram and that it remained in the family after his death having passed to his widow.

The purchase of Buckland and Charlton mills in 1799 and the handing over of the Town Mill to Thomas (3) in 1800 suggests that Thomas (2) died at about that time and that Ingram, an elderly man, was putting his house in order. From the wording of the conveyance quoted above it is clear that Ingram became the owner of Buckland Mill following its sale by the Church and that he passed it on to Thomas (3).

Some time during the period 1790/1799 Buckland Mill is reported to have suffered a fire and was enlarged. It is thought that it is during this period that Buckland (Bridge) house was built to house the Horn family.

The Charlton Mill owned by the Horn family was not the site of the paper mill which C.P. Davies refers to as Spring Garden Mill. In 1746 Charlton Mill was held on lease from the Archbishop of Canterbury by Thomas Horn the elder and in 1799 Thomas Horn (3) bought it. Here he built an oil mill concerning which the Kent Gazette of February 1805 announced "Charlton Oil Mills, near Dover. Linseed Oil cakes are now selling at the above mills at fourteen Guineas per thousand". He sold the business in 1807 to Willie Cullen, tanner of Dover, who died in 1811. The mill changed hands several times over the years and in 1865 was purchased by George Chitty, a corn miller of Deal, and remained in the family until it was destroyed during WW2.

It was during this period that there are signs that Thomas (3) was bearing responsibility for the paper mill although Ingram still appeared to be actively involved. In 1806 there was labour trouble at the mill as evidenced by the following advertisement in the "Kentish Gazette"; ABSCONDED from the service of Mr Thomas Horn to whom they were apprenticed, William Hedgecock, papermaker, 20 years of age, about five feet six inches high, stout made, round face, of a hobbling gait and wears his own hair short. Thomas Charles Read, papermaker, aged 16 & 19 years, about five feet eight inches high, pale complexion and wears his own hair short. If they will return to their master’ a service within a week from this day, they will be received and forgiven, but after that time a reward of FORTY SHILLINGS each will be paid on apprehending them and whoever harbours them after that day, will be prosecuted.

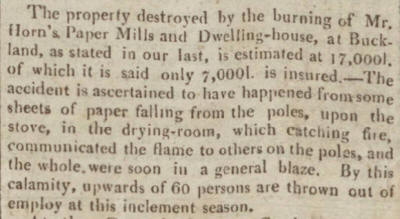

1814 - On the 6th January 1814, Buckland Mill was burnt down.

A report by the Kentish Gazette states that the fire was caused by - " sheets of paper falling from the poles upon the stove in the drying room ".

A second report from the Kentish Gazette States - "The calamity is the more to be deplored as upwards of fifty persons are in consequence thrown out of employ at this inclement season of the year ".

Another report of the fire from the Sussex Advertiser shows...

Journalists of today are sometimes accused, justifiably, of exaggeration and this may well have been the case in respect of the unemployment caused by this fire all those years ego. The mill is believed to have been small at the time and its output limited. There is no evidence that the mill produced white paper at the time and it is doubtful if it could have supported fifty workers.

A week after the fire the following letter appeared in the Kentish Gazette

"Impressed with gratitude for the very prompt and great exertions of those gentlemen who, by their example, and with the united efforts of numerous others, to arrest the progress of the flames at the late calamitous destruction of my manufacturing and dwelling house at Buckland, and who rescued from the devouring element part of my property, I beg to offer my sincere thanks and also to the officers and privates of the Dover Garrison, whose appearance at the spot -very early after the alarm, and by their activity and long continuance rendered me most essential services".

The letter was signed by Thomas Horn and the address was given as ‘Buckland House’. This house was renamed Buckland Bridge House when the Buckland House which stands today was built several years after the fire.

Buckland Mill was rebuilt after the fire and considerably enlarged and it was in this year that the last evidence of Thomas Horn appears. The keystone of an arch over the waterwheel race bears the inscription T.H 1814 and remains today as a monument to the endeavors of the Horn family.

1817 - The rebuilt mill was offered for sale in an advertisement published in the Kentish Gazette, it reads

"A capital freehold paper mill - having a large breast shot water wheel - supplied by a powerful stream, capable of working six vats, with presses, drying lofts -- it has a space for another water wheel and a reserved convenience for putting up a machine ".

The advertisement also states that the proprietor " parts with the concern solely on account of his retiring from business ". The advertisement also states that those seeking further particulars should apply to Mr Bryan Donkin, engineer, Fort Place, Bermondsey. It is of particular interest to note that the Horn family, in spite of their active business interests over the years had not followed the example of their neighbour William Phipps and installed a papermaking machine. The matter appears to have received some thought by Ingram Horn when the mill was rebuilt after the fire.

In the following year, 1818, the mill was offered of lease and in 1820 it was put up for sale by auction. The particulars stated that the whole is now in the occupation of Mr Thomas Horn who is retiring from business " and further that there were " three vats at this time at work on blue and brown paper and a thorough completed for another wheel sufficient to drive two white vats - -. If required the mill, will drive three pairs of stones and dressing tackle ". The ‘reserved convenience’ for putting up a machine remained.

1822 - Buckland Mill was occupied by George Dickinson the younger brother of John Dickinson of Croxley.

George Dickinson’s career as a papermaker in the Dover area extended over a period of 15 years, during which time he occupied three mills, Bushey Ruff, Buckland and Charlton. He was born in 1795 and 1818 he joined his brother John in his papermaking business.

The nature of George Dickinson can best be understood by quoting from " The Endless Web " by Joan Evans which deals with the House of Dickinson from its inception. She writes as follows :

" In 1818 John Dickenson's mother, in return for a loan, had insisted on John taking her youngest son George into the Mill. He was an awkward, difficult, loutish youth and a great trial to his sister in law and brother, with whom he lived at Nash House for some years after 1818. Ann"(John Dickinson's wife), " in particular despised what she called his eye service and lazy disposition".

On the 19th Jan 1821 she records: "Mr D had a letter by coach to say all the east Indian ammunition" (cartridge paper)" was bad, so they will be obliged to take it back at a great loss, owing to George's not attending to it while they made it, at a loss of £200"

A week later, on 27th Jan, she writes: "after dinner they came and told Mr D that there were no logwood chips and in consequence the mill and machines had to wait two days and my poor husband was almost out of his wits he was so worried, it turned out too, that G.D knew that they had not arrived and never took the trouble to stir about it".

Two days later, she continues: "my dear husband much distressed to get the dry work done owing to George's sending away our only two good hands".

On 1st Feb she writes: "walked up to Apsley.... my dear husband found in great agitation having found that during his absence in town George had spoilt the ammunition making for the east I. Cy. being the second parcel he had spoilt for this order. Mr D was quite ill with the worry. The consequence is that not half the order can be sent up today and it has every prospect of being rejected and they are obliged to make more of it".

Trouble continued on March 23rd she writes " G.D. was very impertinent to my dear Husband. this morning on his saying that if some paper was not forwarded we shall lose the East India business. What will be the up-shot of this brutal conduct I cannot imagine but I am sure it is enough to drive him mad to have such a savage deal with him.

It is clear that John Dickinson wanted to be free of his brother but to accomplish this he required capital to repay the loan from his mother on his brother’s account. The sum required was substantial for Joan Evans records that " Andrew Strakan lent him 12,500 and negotiations continued, neither easily nor happily".

The money must have been raised for in August 1822 John Dickinson visited his mother and made arrangements for George to rent Buckland Mill. George left for Dover in December 1822 at the age of 25 with, as far as is known, only four years of papermaking experience behind him, to build a local empire.

He must have been a young man of big ideas for John’s wife Ann, records on the 2nd November 1822, before George had left to take over Buckland Mill, their horror at his extravagance in buying a 10 horse power steam engine from Birmingham for the mill, and two machines before he had a certain vent for his paper ‘.

It will be recalled that when Buckland Mill was offered for lease the advertisement indicated that there was a "reserved convenience for pitting up a machine"

George Dickinson was not content with the occupation of Buckland Mill and by 1826 it is known that he occupied Bushey Ruff Mill and in 1833-34 he built a steam paper mill at Charlton. Joan Evans makes it clear in The Endless web that he came to Dover in order to carry out papermaking at Buckland and it would appear as if he had substantial financial support from his mother. His sister-in-law wrote of his purchase of two machines before he actually left for Dover which may indicate that he had ideas of extending his activities to a mill or mills other than Buckland. It may be safely assumed that one of these machines was installed at Buckland.

Bushey Ruff never had a machine and Charlton 'steam paper mill' is reported as being built in 1833-34, some ten years after Dickinson arrived at Dover. The date when he took over Charlton mill is not known but it is known that one James Brook is named in the Excise list of 1832 as the occupier. However, in 1825 Dickinson is reported to have been negotiating for land at Charlton on which he subsequently built himself a large house, later to become a part of the old Dover Hospital.

Joan Evans relates how George Dickinson entered into competition with his brother John in making a ‘laid’ paper in an endeavour to imitate hand made paper. She records that Ann Dickinson wrote on the 10th. September 1823 in her diary:-

"heard from dearest (John) G.D. at some of his dirty tricks again trying to get rich to make him a laid roll and in consequence dearest tormented by his mother.

On 5th March 1824 she wrote: ‘"Had long letter from dearest giving an account of the wretched paper George has sent up for laid paper in imitation of his"

The above clearly indicates that George Dickinson installed one of the two machines his sister-in-law records he ordered in November of 1822 at Buckland and that it was operating during the following year. In the year after she had recorded that ‘ George had sent up some wretched laid paper' John and Christopher Phipps of Crabble Mill patented the laid dandy roll. In 1828 George Dickinson patented an improvement to the papermaking machine by giving a vertical motion to the endless web where it first received the pulp and in 1833 he patented a way of making laid paper by using threads or yarns instead or wires.

George Dickinson became bankrupt in 1837 and died in 1843. The year after his bankruptcy Buckland Mill was again advertised to let. It was described as "most eligible and desirable" and " famed for the quality of its paper". It had a wheel seventeen feet in diameter, four engines, three machines "with requisite chests, a steam boiler, fourteen presses, a bleaching room and apparatus, a drying loft about one hundred and forty feet long fitted with trebles and linen". Permission to view was to be obtained from Mrs Horn so presumably by this time Thomas Horn was dead. The Tythe schedule of 1840 records that the mill, was occupied and owned by the " devisees of Thomas Horn".

This advertisement provides conflicting evidence to the assumption above that a papermaking machine was installed in 1823 but this may be explained by accepting that the "three machines" were in fact the three vats which were installed when the mill was advertised in 1820. The papermaking machine was probably the property of the creditors of Dickinson. It is of particular interest to note that in 1820 the mill was at work on blue and brown paper " but when offered to let in 1838 after Dickinson’s tenancy it was described as being famed for the quality of its paper In addition it had a bleaching room and apparatus.

From Kentish Gazette - 20 March 1838

Dickinson was clearly progressive by his introduction of white papers to Buckland and his financial failure was probably due to his Charlton (Paper) Mill venture.

From the evidence presented above the following imaginative conclusions are offered.....

At the time of the fire in 1814 Ingram Horn must hare been a very old man for it is known that his father died between 1746 end 1750.

It is also known that he and his brother Thomas (11) were found acceptable to receive an indentured apprentice in 1746. Thus Ingram was probably well in his eighties in 1814.

The description of the potential of the rebuilt mill when it was offered for sale in 1817 with a possible six vats, an additional water wheel end the reserved convenience for a machine may have been the dream of Ingram Horn and the fact that Bryan Donkin was associated with the advertisement of sale may be an indication of his intention to install a papermaking machine.

The fact that the mill was offered for sale just three years after the fire and its rebuilding would appear to indicate that Ingram died at about that time.

It is clear that Thomas Horn, probably the son or nephew of Ingram, wished to retire and there is no evidence of his having had a son to carry on the business. That he was married appears certain because of the mention of Mrs Horn when the property was offered for let in 1838. He appears to have had a daughter who married William Fleet for in the conveyance referred to above, after the names or Ingram Horn and Thomas Horn we find Ann Horn, (probably the latters widow), William Hussey Fleet, (probably a son-in-law), and Thomas Horn Fleet, (probably a grandson of Thomas and Ann Horn).

After the failure of Dickinson the mill appears to have remained unoccupied for several years. The Tythe schedule of 1840 records this fact and that it was owned by the " devisees of Thomas Horn"

1846 - In 1846 the mill was occupied by Mr Weatherley, the brother of William Weatherley who bought Chartham Mill, in 1790. William Weatherley died in 1849 and was succeeded by his brother and in the same year Buckland Mill was sold to Charles Ashdown. There appears to have been some obscure terms associated with the sale to Charles Ashdown paid some form of rent on Buckland Mill for many years after the purchase.

1849 - In a letter from him to Henry Hobday thirty years later when a partnership was under discussion he wrote about conditions at the mill when he purchased it in 1849

"The first year I paid £500 for rent, the next year £400 and then weatherly failed and I paid £300 per year and I then paid £250 for about twenty years"

So did not say to whom he paid these annual sums or why Weatherley was involved.

The sale was a direct one, as far as can be ascertained, between the Horn family and Ashdown and there is no doubt but what Weatherley leased the property prior to the sale. The mention of Weatherley having failed in the third year coincides with a serious fire at Chartham Mill to which he had returned after the death of his brother, whose estate he appears to have inherited.

Another extract from the letter referred to above reads thus:

"I have been here thirty years next August and had you seen the place then and see it now. I have laid out upon the mill £5,000 besides what it cost me to buy"

It is suggested that Weatherley made a deal with the creditors of Dickinson when he leased the mill from the Horn family regarding the purchase of the papermaking machine, and perhaps other equipment, over a period of years. His obligation to the creditors seems to have been assumed by Ashdown when Weatherley "failed" in 1851, the year when the fire destroyed Chartham Mill. Weatherley’s financial difficulties are recorded in historical notes of the Chartham Mill. In March 1851 he borrowed £7,500 on a bond of 5 per cent from Charles West, a papermaker of Sheffield Mill, Burghfield, Berks, to whom the mill was also mortgaged as further security. By December of that year he had expended that sum to West ‘s satisfaction and had received a further advance of £3,500 Weatherley died the following year.

1877 - Charles Ashdown’s son Henry, who ran the mill for his father, died. His other son Charles, who worked in a local bank, came into the business with his father but, lacking practical experience, was confronted by many difficulties. Charles Ashdown senior offered Henry Hobday (at the time General Manager of Snodland Mill) an equal partnership in the business with his son. Henry Hobday accepted and the business traded under the name of Ashdown & Hobday.

The partnership was a success and the business prospered. Paper production rose from two tons to seven tons per week while the range of papers made was wide, from browns to banks and ledgers with a prosperous ‘country’ sale of bags and wrappings to shops throughout South East Kent. Then a disastrous fire occurred in 1887 which destroyed much of the mill.

From an account in the Dover Express dated September 1887 it appears that until 1879 the water power available was sufficient to drive the machinery in the mill but after that date two steam engines were installed, the main one of 50 Horse Power which was " completely destroyed " by the fire and one of 14 Horse Power which was "not much damaged ". There were five rag washing and. beating machines " of the most approved make built by Piper of Maidstone " and other gear -- " the most pitiful wreck is the papermaking machine, which is a long apparatus of about seventy skeleton reels ". About fifty hands are said to have been put out of work.

The mill was rebuilt and operating within nine months with a weekly output of twelve tons but much business had been lost and finances were low. For three years Ashdown & Hobday struggled on, slowly improving their position and in 1890 they accepted an offer from Wiggins Teape & Co. to buy the mill for £20,000. From then on progress was rapid.

1892 - No. 2 papermaking machine was installed and in 1894 the old Crabble Mill, where William Phipps had installed a papermaking machine in 1807, was bought and turned into a rag preparation department for Buckland Mill. The Crabble Mill was burnt down in 1905 and rebuilt.

1911 - No. 3 papermaking machine was installed for the main purpose of making "Conqueror" Ledger papers.

With regard to Buckland Bridge House, it is known that it was occupied by Charles Ashdown senior in 1881 and by his son Charles in 1890 before moving to Loudwater when Buckland Mill was sold to Wiggins Teape. The house was then used to accommodate a foreman and finally pulled down in 1897 to provide room for a new stock room.

The history of Buckland Mill from the time of the partnership of Ashdown & Hobday until the 1930s is best told by the biographical notes of Henry and Lewis Hobday which follow their lives became so much a part of the mill as to become a part of its history.